The Institute Presents: The EU Elections

- Multiple Authors

- Jun 5, 2019

- 51 min read

Overview: Philippe Lefevre

We have just experienced what many have called, the most European EU elections ever. With turnout rocketing upwards to over 50% [1] and many pan-European issues being raised vigorously from across the Union. However, for many European citizens, it was local issues that affected their vote, from their countries place in Europe, to the parties themselves. In this special presentation we at the Institute want to give you the chance to hear from every member state what the outcomes of the elections were for each country, from recently embattled Austria to rather peculiarly, the United Kingdom.

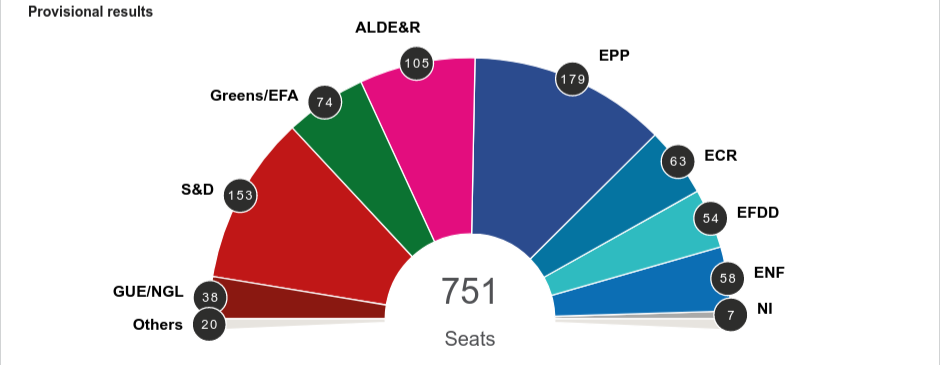

First we must begin with a brief overview of the results themselves. In essence, it was a battering for the traditional two main parties of the EU Parliament, the European People's Party (a centre-right grouping) and the Socialist and Democrat Party (a centre-Left grouping). In almost all EU elections previously, the two parties together have managed to secure at least half of the seats in the parliament (There are 751 MEPs total) but this was narrowly missed this year, with the Alliance for Liberals and Democrats in Europe (a roughly liberal centrist grouping) gaining many seats along with the Greens. This strong show of force for pro-EU groups was offset by strong returns for Eurosceptic groups in Parliament, spread across multiple parties. However, if you dig deeper into the countries themselves, you find many different interesting results that allow you to understand the nature of these elections and their impact on the future of European politics.

The EU election results as a whole, still provisional but unlikely to change. [2]

[1] “Turnout | 2019 European Election Results | European Parliament.” 2019 European Election Results. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://www.election-results.eu/turnout/.

[2] “Home | 2019 European Election Results | European Parliament.” 2019 European Election Results. Accessed June 5, 2019. https://election-results.eu/.

Austria: Natalie Raidl

Like in most other countries in Europe, the turnout in Austria’s elections to the European Parliament was considerably higher than in the previous election – almost 60% in 2019 compared to 45% in 2014. While all of Europe was bracing for a sweeping victory of right-wing parties, Austria’s FPÖ (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs) was caught up in one of the biggest political scandals of Austria’s history. Party leader Heinz Christian Strache was filmed during a meeting with a supposed Russian oligarch’s niece and caught on camera vowing to politically staff the biggest Austrian newspaper and sell out the Austrian building industry. This was followed by Mr. Strache’s withdrawal from his post as vice chancellor and the along with him, all FPÖ ministers stepped down. The chancellor called for new elections, and the transition government was given a vote of no confidence, forcing the president to put together an expert government to run the country until elections in September.

This national crisis overshadowed most of the European elections and may also have impacted the high turnout, as people’s political awareness was high around the time. The outcome of the elections were used as a measure for who would end up benefiting from this national crisis and who would lose political popularity. The strongest party was the Austrian People’s Party (Österreichische Volkspartei, ÖVP), who scored 34,55%, a phenomenal 12% increase compared to 2014. This suggests that party leader Sebastian Kurz was able to convince his electorate that he was the “good guy”, who took al necessary steps to rid Austria of corrupted politicians. As expected, the FPÖ lost – but only around two percent from 19,72% in 2014 to 17,20% in 2019.

This shows that Austria’s right-wing party has a very strong core electorate that cannot even be alienated through a video that shows the party’s leader in treasonous behavior. The Austrian Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreich, SPÖ) scored 23,9%, practically the same result as in 2014, which nevertheless was a disappointment. The party was hoping to benefit from the crisis by being viewed as the strong opposition who forced out the untrustworthy transition government. However, it seems like the Austrian population, who were largely against this vote of no confidence, did not appreciate this move. The Austrian Green party, who had not received enough votes in the previous parliamentary elections to enter parliament, celebrated a big victory, scoring 14,08%. The centrist liberal party NEOS received 8,44% in their first run for European elections, which was a slight increase to their score in the national elections. The Austrian communist party and the “JETZT!” list did not make the threshold and will not be represented.

Belgium: Stijn Mertens

Belgium went to the voting booth on the 26th of May to vote for regional, national and European representatives. After Climate Marches, ‘Gilets Jaunes’, the fall of the government because of the Global Compact for Migration also known as the Marrakesh Pact and multiple shortcomings in the Belgian justice systems, we could only guess which theme would come to dominate the campaign. Most expected growth for the Greens (Groen & Ecolo), the extreme right (Vlaams Belang) and the extreme left (PTB - PvdA) at the expense of the establishment parties. The magnitude of this growth remained to be seen.

The results came in and they shocked us. In Flanders, ‘Vlaams Belang’ went from 5.9% (the electoral threshold lays at 5%) to 18.5% of the votes, making it the second largest party after the conservative nationalist party ‘N-VA’. ‘Groen’ underachieved and only gained 1.4% and the communist ‘PvdA’ reached the electoral threshold for the first time in Flanders. Meanwhile in Wallonia things went in an entirely different direction. Here large gains were made by ‘Ecolo’ (+6%) and ‘PTB’ (+7.5%) making them the third and fourth party respectively after the socialist ‘PS’ and the liberal ‘MR’. Note that there are no significant right-wing, anti-migration parties in Wallonia, quite unique in Europe nowadays.

The winners and losers on regional, national and European level are roughly the same. In both regions coalitions can be formed rather easily. A left-wing or progressive coalition in Wallonia and a conservative one in Flanders. The federal level will not be as straightforward. It requires at least one party from the Wallonian and the Flemish side, so all major language groups are represented. Add to this that most parties signed an agreement not to make a coalition with ‘Vlaams Belang’ (=Le Cordon Sanitaire). This agreement effectively eliminates the third largest party from a possible coalition. As things stand, at least four parties are needed to form a majority on a national level. In this scenario ‘N-VA’, ‘PS’, ‘Vlaams Belang’ and ‘MR’/’Ecolo’ would have to make a coalition, which could never happen. Let’s hope we do not break the record for the longest government formation again.

Bulgaria: Ana Popova

From Bulgaria, seventeen new members from five different political formations are going to be sent to the European Parliament (EP).[1] The governing party in the country, Citizens for European Development (bulg. GERB) reached the highest results with 31,07 % and won 6 MEPs. Even though the number of their candidates doesn’t increase, they have scored a slight increase in the votes compared to the 2014 EP elections.The biggest opposition party at national level, the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), followed with 24,26 % and 5 MEPs – one more MEP than the last election. This is an increase of approximately 5% of the votes compared to the 2014 elections.

The Movement for Rights and Freedoms (bulg. DPS) gets to send 3 members of the EP with 16,55 % of the votes. This is a negative result for the party that is supposed to represent the Bulgarian minorities and means that they will have one member less than in the previous election. The first two candidates who got the most votes withdrew their candidacy after the elections. The first one and current chairman of the DPS, Mustafa Sali Karadayi, explained in his questionable Bulgarian that their goal was to unite their voters. For the second candidate, Delyan Peevski, this is the second withdrawal after he cancelled his candidacy in the 2014 EP elections as well. His argument was that he was needed more in the Bulgarian Parliament, where the times he has been physically present since his inauguration in 2017 can be counted on one hand. The Bulgarian nationalists’ movement “Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation” (bulg. VMRO) has won 7,36 % of the electorate and will be represented in the EP by 2 MEPs.

A newly formed coalition of the Bulgarian Green party, the party “Yes, Bulgaria!” and the Democrats for Strong Bulgaria (DSB) also made it above the 5,88%-hurdle with 6,06% and will have one MEP – the leader of DSB Radan Kanev. The results are positive for the Greens in comparison to the 2014 elections.

In contrast to the overall positive results regarding the voter turnout, the election participation was lower in Bulgaria compared to earlier elections. Only 32,64% of the population granted a valid vote, which is 3,2% less than the 2014 elections and 6,35% less than the 2009 elections.[2]

The EP elections are often regarded by theorists and academics as “second-line-elections” which are not believed by the population to influence national politics. Consequently, many voters view them as a pitch mostly to a protest vote. [3] This observation is accurate in the Bulgarian elections results only inasmuch as an insignificant percent of GERB’s electorate has chosen to support the Green and Democrats Formation instead. Otherwise, there is no significant change in comparison to the national elections.

[1] Bulgarian Central Electoral Commission, European Parliament Elections 2019, https://results.cik.bg/ep2019/mandati/index.html (accessed 02.06.2019).

[2] European Parliament, Elections Results 2014, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/elections2014-results/en/country-results-bg-2014.html (accessed 02.06.2019).

[3] Todorov, Antonii, “European Elections 2019: The earthquake ist postponed, but for how long?”, https://antoniytodorov.wordpress.com/EP elections

Croatia: Filip Fila

Although end results did not deviate a great deal from predictions, much commotion regarding them ensued in Croatia in the days following the elections. The most popular Croatian party and the main party within the ruling coalition, the center-right Croatian Democratic Union, earned the greatest share of votes (22,72%) and consequently won 4 seats in the European Parliament. They had, however, certainly hoped to win more seats than their longstanding rivals, the center-left Social Democratic Party, which got 18,71% of the vote, and was also awarded with 4 seats. All other parties which passed the elective threshold won a single seat. It should, however, be noted that the third place belongs to a coalition of right-wing parties titled Croatian Sovereignists, led by the former/current EP MP Ruža Tomašić. They managed to win 8,52% of the vote. Coming in close with 7,89% of the vote was the independent candidate and newcomer to politics Mislav Kolakušić, the biggest surprise of the elections. The last two seats will be reserved for the the anti-establishment Human Shield party and the Amsterdam Coalition, which consists of several center-left, liberal, and regionalist parties. There was not a great difference between the two in terms of votes won; Human Shield was the top choice of 5,66% of the voters, while the Amsterdam Coalition acquired support from 5,19% of the voters. Voting turnout was fairly low, a bit under 30%.

Analyzing the results, what is noticeable is that an exact correspondence with popularity polls and with the results of recent national elections did not occur. Therefore the CDU, which expected to win 5 seats and a greater share of the vote, has been perceived as one of the losers of these European elections. SDP, on the other hand, should rightly see themselves as winners, even if they do not seem to be anywhere near close rivaling CDU on a national level. Owing to the strong lineup of politicians they fielded, they will not only now have the same amount of seats in the EP as CDU, but have increased their number by 2. Concerning other parties and their expectations, the Human Shield stands out as it has been itching to become Croatia’s second most popular party, but was ultimately miles away from SDP this time around. Among those which failed to win a seat, many noted the bad result of the Bridge of Independent Lists, a relatively new conservative party which peaked in its first elections ever in 2015, but has since then been on a decline. On the whole, the waters of future national elections seem muddy as what was once more demonstrated was fragmentation as a reflection of a sort of a desire for new options to counter the CDU and SDP. Despite the resurgence of SDP, what should also be highlighted is a general shift towards the right. As far as European politics are concerned, Croatian representatives will be predominantly pro-European, with the only explicitly Eurosceptic option being the Human Shield and its MP.

Cyprus: Lawrence

The results of the European Parliament electoral process in Cyprus proved that still, European affairs are far from the Cypriot reality. The panel debates leading up to the elections were mostly focused on inter-party bickering, discussions on local topics (national health care, crime, etc), less about the Turkish invasion problem (with the exception of the latest Turkish invasion of Cyprus’s Exclusive Economic Zone and deep-sea drilling – look it up), and even less coverage of European affairs. Which is why it was not entirely surprising that Cypriots ignored the #thistimeimvoting campaign of the European Parliament, and chose instead to vote for the beaches rather than spend their Sunday involving themselves in a process that has intentionally kept them distant. If nothing else, it showed that when people are called to vote for the future of Europe, they should be involved in it from the beginning.

The most surprising result of the Cypriot vote was the “douze points” given to a Turkish-speaking Cypriot, who, for the first time since Turkish-speaking Cypriots walked out of their public service posts in 1963, will hold a public office seat representing the interests of the Republic of Cyprus. Turkish-speaking Cypriots were the largest minority on the island, when it became a Republic in 1960. Following an internal conflict caused by years of British oppression, a Greek-led military coup and a Turkish-led invasion in 1974, the Turkish-speaking Cypriots have ever since been living in the north of the island, forming a de facto state only recognised by Turkey. Now, for the first time, an individual who holds a passport of this de facto state, as well as a passport of the Republic of Cyprus, is elected as 1 of the 6 Cypriot MEPs, even though he does not reside in the areas controlled by the Republic of Cyprus. Whilst this reinforces the power of the Republic of Cyprus and diminishes any status the puppet state of the north has had, many fear about potential security and national issues that may arise.

The other highlight, although much less surprising, was the lack of any women candidates. Showing how the party politics on the island are still male-dominated, the society has a long way to go until it realises that women bring unique qualities and skills to the negotiating/political table.

The newly elected group of 6 MEPs will need to produce a lot of work to prove to their European counterparts that the island is indeed European, but they will need to put an even greater effort in achieving at least a fraction of their pre-electoral promises to the Cypriot people.

Czechia: Anna Korienieva

Interest in the European Parliament elections has historically been low in the Czech Republic. This year's turnout was 28.72%, which is significantly below the EU average of 50.8%. Such a situation reflects prevailing Euroscepticism, which generally benefits pro-European parties, whose supporters are more likely to take part at the election to support their favorites.

With regard to the election results, the main power of the current Czech government, ANO (YES 2011), won 21.18% of the vote resulting in 6 MEP seats. Party's slogan “We will protect the Czech Republic, steadily and uncompromisingly" suggests its main priority – to defend the Czech Republic against the external enemy, embodied in Brussels and EU regulations. This is also connected to the adoption of the Euro, which Prime Minister Babiš (ANO) committed to postpone during his election campaign, a move seen to have been made to attract more voters

However, the question is to what extent ANO will be able to fulfill its promises in light of recent events associated with the prime minister's case, which came to the attention of the EU and the last Commission's verdict was not particularly favourable. Moreover, the EU's current focus is drawn to the rule of law, especially in relation to violations of EU legislation by Poland, Romania and Hungary. Combined together, those factors will most probably translate into greater efforts by net contributors to the EU budget to better monitor the flows of subsidies. The above mentioned factors would likely hamper achieving the Czech government's priorities: to continue receiving as much money as possible to support its agriculture as well as its poorer regions.

ODS (Civic Democratic Party) came second in the elections and thereby proved its position of the strongest opposition party. This fact, along with the ČSSD's (Czech Social Democratic Party) debacle, clearly indicates growing dissatisfaction of the prime minister’s policies among voters. However, despite intense political climate and the growing unrest as a result of the government's disregard of democratic values, the party’s goal of winning the next parliamentary elections is becoming increasingly unlikely. In the past, Andrej Babiš managed to cope with political turbulence and his party currently dominates the Czech political scene despite week-lasting anti-government protests.

Regardless of the fact that the S&D socialist faction came second on a pan-European level, on the domestic level Czech Social Democratic Party did not gain enough support to make it to European Parliament. This was largely due to the shocks of the internal political scene and the inability to face them quickly, which signals serious future problems to come.

Significant in the elections was the strengthening of TOP09 + STAN and Czech Pirates. Their ability to further cooperate will be decisive with regards to the fate of the current government.

Despite the low turnout, it can be said that the results of the EU parliamentary elections more or less reflect current power distribution. However, given recent events on the Czech political scene it is hard to speculate with great assurance how things will develop going forward.

Denmark: Arvid Rhod Joensson

The build-up and outcome of the Danish election for the European Parliament can be boiled down to four key points:

1: The reformists and eurosceptic parties lost public support. Dansk Folkeparti (ECR) went down from four to one seat and the anti-EU party Folkebevægelsen mod EU (GUE/NGL) lost its seat to Enhedslisten (GUE/NGL). The biggest electoral winners are the centre parties; Venstre (ALDE) and Socialdemokratiet (S&D), winning four and three seats respectively. Det Konservative Folkeparti (EPP) and Radikale Venstre (ALDE) occupy one seat each.[1] The loss in support for anti-EU parties is affected by the scare Brexit caused, as Danish and British EU sentiments somewhat match.[2] Denmark is reluctant to fully engage in the European project politically and financially. As an example of this, Denmark still has its own currency and has opted out of EU regulation on home and justice matters.[3]

2: The fear of climate change completely overshadowed the fear of refugees and immigration. The Green party gained 13% and two seats.[4] All left-leaning and centre-right parties made climate politics a top priority.[5] These parties had paid only lip service to the topic until a few months ago, but public sentiment forced the parties to discuss the issue and come up with possible solutions. Whether the parties will remain committed to this issue remains to be seen.

3: Taxation of multinational corporations became the top priority for many Danish parties.[6] Income tax and company taxes are high in Denmark and Danes want companies like Coca Cola and Google to abide by the same rules. The issue has occasionally been discussed, domestically and in the EU, for the last ten years or so.[7] The EU took further steps to solve the problem in 2016 and the Danish representatives may help speed up this legislative process.[8]

4: The election turnout went from 56% of the eligible electorate in 2014 to 66% in 2019.[9] The Danish population therefore seems to have grown more interested in European politics, which is the result of Brexit and climate politics.[10] There are no signs, however, that the public has grown more favourably disposed towards becoming more integrated in the EU.[11] Danes want cooperation, but with a large degree of independence.[12]

With thirteen seats (fourteen after Brexit), the Danish representatives are too few to play a major role on the European scene, but there is one way in which Denmark has influence. The current Commissioner for Competition, Margrethe Vestager (ALDE), has made a big name of herself in her fight against multinational corporations such as Google.[13] She is currently one of the five major candidates for the highest positions within the EU, and there are no signs that she will retire anytime soon from the zenith of European politics.[14] In the end, the Danish people are likely soon to lose interest in the grander European project and in solving the problems of climate change collectively. The question of refugees/migrants and other domestic issues will soon be the focal point of the general public once more. Only time will tell if the Danes stay committed and invested in EU cooperation.

[1] European Parliament, “2019 European Parliament Election: Denmark”, https://election-results.eu/denmark/ (Accessed 30/05/2019)

[2] Emma Qvirin Holst, ”EU Overblik: Historisk Stor Opbakning til EU blandt Danskerne”, Altinget, https://www.altinget.dk/artikel/eu-overblik-historisk-stor-opbakning-til-eu-blandt-danskerne (Accessed 31/05/2019)

[3] Jesper Kongstad, ”Trods Brexit Kaos: Historisk Stor Opbakning til EU fra Danskerne”, Finans.dk, https://finans.dk/politik/ECE11327982/trods-brexitkaos-historisk-stor-opbakning-til-eu-fra-danskerne/?ctxref=ext (Accessed 30/05/2019)

[4] European Parliament, “2019 European Parliament Election: Denmark”, https://election-results.eu/denmark/ (Accessed 30/05/2019)

[5] Simon Vincensen, “Klima, Klima, Klima – og Migration samt Mindre EU: Her er Kandidaternes Vigtigste Sager i Aften”, DR, https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/politik/ep-valg/klima-klima-klima-og-migration-samt-mindre-eu-her-er-kandidaternes-vigtigste (Accessed 31/05/2019)

[6] Ritzau, “Røde Partier vil have Fælles Bund under Selskabsskat i EU”, Policy Watch, https://policywatch.dk/nyheder/eu/article11392594.ece (Accessed 30/05/2019)

[7] John Hansen, ”Overblik: Sådan vil EU få Skat fra Multinationale Selskaber”, Politiken.dk, https://politiken.dk/oekonomi/fokus_oekonomi/Luxembourg_laekage/art5609135/Overblik-S%C3%A5dan-vil-EU-f%C3%A5-skat-fra-multinationale-selskaber (Accessed 31/05/2019)

[8] Peter Birch Sørensen, “To Harmonise or Not to Harmonise? A Comment on the European Commission’s Study on Company Taxation”, KU.dk, pp. 1-5. http://web.econ.ku.dk/pbs/Dokumentfiler/Comments%20(English)/Companytaxstudy.pdf, (Accessed 31/05/2019)

[9] European Parliament, “2019 European Parliament Election: Denmark”, https://election-results.eu/denmark/ (Accessed 30/05/2019)

[10] Simon Baastrup, “Klimakamp, Brexit, Trump og Russiske Trolde: Danskere Bakker op om EU som aldrig før”, Politiken.dk, https://politiken.dk/indland/art7158022/Danskerne-bakker-op-om-EU-som-aldrig-f%C3%B8r (Accessed 31/05/2019)

[11] Erik Holstein, ”Ny Måling: Vælgerne vil blive i EU, men de vil ikke af med Forbeholdende”, Altinget, https://www.altinget.dk/artikel/178869-danskerne-rykker-mod-midten-i-eu-politikken (Accessed 31/05/2019)

[12] Bjarke Møller, ”Hvad Føler Danskerne for EU?”, Tænketanken Europa, http://thinkeuropa.dk/vaerdier/hvad-foeler-danskerne-eu (Accessed 31/05/2019)

[13] Ritzau, “Vestager Åbner Sag om Britisk Skat på Multinationale Selskaber”, Fyens.dk, https://www.fyens.dk/udland/Vestager-aabner-sag-om-britisk-skat-paa-multinationale-selskaber/artikel/3197811 (Accessed 30/05/2019)

[14] Mathias Sonne, ”Vestager & de Andre: Fem Mulige Kandidater til EU-Tronen”, Information, https://www.information.dk/udland/2019/05/vestager-andre-fem-mulige-kandidater-eu-tronen (Accessed 30/05/2019)

Estonia: Rainer Urmas Maine

The European Parliament elections in Estonia came at a highly tense moment in Estonian politics. Parliamentary elections were held just two and a half months ago, on 3rd March and even though the election results then were not surprising, the aftermath was. After two and a half years in power, leftist Estonian Centrist Party (Eesti Keskerakond) lost the elections to the former ruling party, liberal Reform Party (Reformierakond).[1] Thus, it seemed that the coalition would probably be composed of those two parties, instead the Prime Minister Jüri Ratas decided to form a coalition with the conservative Pro Patria (Isamaa) and the far-right Conservative People’s Party of Estonia (EKRE).[2][3] This in turn caused a major uproar in Estonia. Reasons for this being that many people did not see how EKRE would be able to soften its rhetoric on classic far-right issues and keep Estonia going in a pro-EU direction. This was highlighted by many scandals which for the most part high-jacked pre-EP elections debates.

Focusing on the European Parliament elections, it is thus necessary to mention that even though there were many debates held on different TV-channels and media platforms, then most of the discussion lead back to whether EKRE is fit to represent Estonia on an international level and whether this government as such should even be in office. Most of the debate in Estonia centred on topics of Estonian politics instead of discussing actual difficult topics on the EU level. Discussions on EU topics were downplayed to a few catchphrases that the party candidates would throw up during their speeches and debates.

The messy situation that the highly controversial new coalition government has generated in Estonia was clearly reflected in the election results for the European Parliament.[4] Coalition government clearly lost votes in the European Parliament elections due to the situation and the opposition clearly won the elections with Reform Party getting 2 seats of the available 6 seats in the elections and the other opposition party, the Social Democrats gaining a seat thanks to the very strong performance of a former Presidential candidate Marina Kaljurand.

The other two seats went to the biggest coalition parties, being the Centrist Party and EKRE.

Curiously enough, Pro Patria originally thought that they had also gotten a seat in the European Parliament, but due to an improper visualisation of the results, this was not the case and after the victory speech on live-TV, they got information from news reporters that they instead would get a seventh seat in the European Parliament if Brexit would go through.[5] This all highlights a very messy election period in Estonia with the coalition clearly losing support in the two and a half months since the national elections. This being a curious case of strong opposition candidates getting record votes and coalition candidates losing a lot of support and a minister having to stand a vote of no confidence already on 3rd June.

[1] Vabariigi Valimiskomisjon. Riigikogu valimised 2019. https://rk2019.valimised.ee/et/voting-result/voting-result-main.html

[2] ERR. Kaja Kallas: Koalitsioon tuleb kas Keskerakonna või SDE ja Isamaaga. https://www.err.ee/916350/kaja-kallas-koalitsioon-tuleb-kas-keskerakonna-voi-sde-ja-isamaaga

[3] ERR. Keskerakonna, Isamaa ja EKRE koalitsioonileppe terviktekst. https://www.err.ee/927401/keskerakonna-isamaa-ja-ekre-koalitsioonileppe-terviktekst

[4] Vabariigi Valimiskomisjon. EP2019 valimised.https://ep2019.valimised.ee/et/voting-result/index.html

[5] Delfi. Europarlamendi valimised võitis Reformierakond. https://www.delfi.ee/news/eurovalimised2019/uudised/saade-blogi-ja-fotod-europarlamendi-valimised-voitis-reformierakond-voimsaima-tulemuse-tegi-marina-kaljurand-kes-kogus-ule-65-000-haale?id=86322903

Finland: Jarkko Nissinen

Six weeks after Finland’s parliamentary elections (eduskuntavaalit) Finnish voters had to elect 13 MEPs (14 after Brexit) to represent Finland in the European Parliament. Nevertheless, the voting percent increased to 42.7 % from 39.1 %. [1] The Finnish nationalists – or True Finns – gained only two seats which is a slight surprise after a sensational result in the Finnish parliamentary elections.[2] The European power duo EPP (Kokoomus) and SD (SDP) held their positions in Finland although the Greens (Vihreät) conquered new electorates, for example, by being the biggest party in the capitol.[3] The Finnish left-wing party Vasemmistoliitto and RKP, the party representing the Swedish speaking minority, were able to hold the fort and won a seat each.

Three topics dominated the Finnish political sphere during EU elections 2019: climate change, immigration and the low voting percent. Ever since the IPCC special report was released the conversation of climate change has been heated in Finland. The Finnish nationalists have framed the report together with any suggestions for a more sustainable way of living as “climate hysteria”.[4][5] The communication strategy paid off in the parliamentary elections, but good luck seems to have ended in the EU elections as True Finns failed to activate their voters. In a similar manner the discussion of immigration has been intense. True Finns are hard-liners on immigration albeit the Finnish center-right parties have updated their views on immigration policies since the last EU elections in 2014.

The low voting percent in EU elections is exceptional in the Finnish scale. Roughly 70 % of Finns voted in the last presidential and parliamentary elections.[1] The Finnish officials were facing a hard task of lifting the voting percent in EU elections while having practically no time to steer the public attention from election to another. Additional element that increased confusion among voters were “double candidates”, in other words Finnish MPs running for MEPs with no intention of taking a seat in Brussels.[6]

The Finnish EU elections 2019 can be concluded in a following way. Pro-EU forces won the race against the Finnish nationalists. The Finnish debate of climate change is now being actualized in votes – and in scale. The Finnish voting percent in the EU elections remains low although finally there was an increase towards – and hopefully far beyond – 50 %.

[1] Oikeusministeriö (2019). [online]. Available at: https://tulospalvelu.vaalit.fi/EPV-2019/fi/aanestys1.html [Cited 2.6.2019].

[2] Mykkänen, P. (2019). Helsingin Sanomat [online] Available at: https://www.hs.fi/politiikka/art-2000006121611.html [Cited 2.6.2019].

[3] Helsingin Sanomat. (2019b). [online] Available at: https://www.vaalikone.fi/euro2019/ [Cited 2.6.2019].de

[4] Barry, E. & Lemola, J. (2019). [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/12/world/europe/finland-populism-immigration-climate-change.html. New York Times. [Cited 2.6.2019].

[5] Helsingin Sanomat. (2019a). [online] Available at: https://www.hs.fi/paivanlehti/28052019/art-2000006122137.html. [Cited 2.6.2019].

[6] Fresnes, T. (2019). Yle Uutiset. [online] Available at: https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-10749255 [Cited 2.6.2019].

France: Vincent Muratet

Following months of anti-Macron demonstrations with groups such as the Gilets Jaunes taking to the streets, the results of the EU elections were far from surprising: La République en Marche (LREM), Macron’s own party created for the presidential election of 2017 [1], came in second with 22.41% of the vote behind that of Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN), who took first place with 23.31% [2].

RN played on the current wave of anti-Macron sentiment, directly presenting themselves as ‘the only list which can make Emmanuel Macron lose and protect the French people’ [3], successfully equating any votes cast for them as being cast in protest against the current President. Unsurprisingly such a tactic was successful, with RN now holding 22 seats on the European Parliament to LREM’s 21 as a result of the elections [2].

In Le Pen’s own words: “Sunday will be a three-way battle. A battle for Europe: say NO to Macron’s Europe. A battle for our nation: say NO to Macron’s politics. A battle for civilisation: say NO to Macron’s vision!”

Despite their defeat, however, Macron’s party can consider itself as having avoided a potential catastrophe [5], with headlines in France claiming that despite the RN having won out, LREM’s base appears stable [4]. Indeed, despite RN’s best efforts to claim the election as a plebiscite and to dissolve the National Assembly (see Jordan Bardella’s tweet below), the election should have little bearing on national politics other than to confirm two truths.

RN’s Bardella: “The French people have sent Emmanuel Macron a very clear message of sanction tonight. We ask that he draw all the conclusions from it, and at least dissolve the National Assembly. He can no longer govern against the French people!”

Firstly that Macron’s presidency is currently unpopular and many in France are dissatisfied - if any confirmation was needed following the Gilets Jaunes, here it is. Secondly, that French politics have undergone or are undergoing a recomposition. In the words of the French Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe: “The ancient [political] divisions are no more, new ones have appeared. It is on these that we must advance from now on: Europe, ecology, growth, employment, social justice.”

Screenshot taken 29/05/2019 at 18:55 UK Time

Hence in national terms, the European elections simply confirmed dissatisfaction with Macron’s presidency, and the shifting of French politics into a slogging match between Macron and Le Pen’s respective parties. On the European stage, however, the rise of the ecologist party Les Verts (LV) with 13.47% and 12 seats [2], combined with an important increase in voters at 51.3% compared to 42.43% in 2014 [6], is incredibly significant.

With the advent of RN, the extreme right gained seats with which to undermine the European Union from the inside. Their opponents LV and LREM (the two being pro-EU parties) could, should they work together when needed, oppose the RN on the European stage. Regarding LV in particular, coalitions in the Parliament itself - perhaps in exchange for aiding LREM against RN - could yield interesting outcomes, especially regarding environmental issues and concerns. Nevertheless, the fact remains that an anti-EU party won out in France, although this fact lessens in importance when one considers that such a result came about due to opposition to the current President.

[1] Alissa J. Rubin (7 May 2017). Macron Decisively Defeats Le Pen in French Presidential Race. - The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/07/world/europe/emmanuel-macron-france-election-marine-le-pen.html

[2] Le Monde (26 May 2019) Elections européennes 2019 : les résultats en sièges, pays par pays, et la future composition du Parlement - Le Monde https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2019/05/26/elections-europeennes-les-resultats-dans-l-ue-pays-par-pays_5467557_4355770.html

[3] Jordan Bardella, and Marine Le Pen (2019) Donnons le Pouvoir au Peuple: Rassemblement National

[4] Solenn de Royer (26 May 2019) Elections européennes 2019 : le RN confirme sa domination, le socle LRM résiste - Le Monde https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2019/05/26/europeennes-le-rn-vire-en-tete-talonne-par-la-liste-lrm-modem_5467603_3210.html

[5] Alexandre Lemarié, Olivier Faye (27 May 2019) Avec les européennes, « la recomposition politique se poursuit, elle s’accélère même » - Le Monde https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2019/05/27/avec-les-europeennes-la-recomposition-politique-se-poursuit-elle-s-accelere-meme_5467978_823448.html

[6] Matthieu Goar (26 May 2019) Elections européennes 2019 : une participation estimée à 51,3 % en France- Le Monde https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2019/05/26/en-france-la-participation-est-estimee-a-51-3-mobilisation-inedite-pour-les-europeennes_5467606_823448.html

Germany: Robin F.C. Schmahl

Though the interest in the 2019 European elections and the resulting turnouts (~61%) have never been higher in Germany since 1989 [1] the Christian democrats [CDU/CSU] as well as the social democrats [SPD] experienced both historical lows. (CDU/CSU: 28,9%, 29 Seats; SPD: 15,8%, 16 seats) [2]. The SPD was suffering from an ongoing political fatigue resulting from a perceived neoliberal stance and assimilation to its CDU/CSU coalition partner [3]. As the Chairman of the Youth Wing of the SPD, Kevin Kühnert, was provoking with more radical leftist ideas, the huge rift within the party became apparent, which alienated potential as well as traditional voters [4].

Similarly, the CDU, though conducting a somewhat effective campaign with EPP candidate Manfred Weber, lost their base on the right, due to Angela Merkel’s liberal stance on immigration, whilst not investing enough into climate policies to convince younger voters [5]. Additionally, the CDU/CSU and SPD were suffering from a recent social media controversy, as both parties weren’t able to produce a convincing reaction to several youtubers calling for a boycott of both parties, which in turn displayed the estrangement of the popular parties from younger voters and modern media [6]. It is unclear what lies in the future for both parties, though they have to find convincing answers to the following questions: Will there be an unchanged continuation of the great coalition, or will the SPD try to break loose in order to regain its position on the left? Can the CDU/CSU profit from the possible election of Manfred Weber as the new President for the EU’s commission? How will both parties reconnect to their traditional base, while appealing to younger voters?

The German Greens were the clear winners of the election with a historical high of 20,5% (21 seats). profiting mostly from alienated young, liberal SPD and CDU voters, but also from former non-voters [7]. The Greens successfully managed to present themselves as the only party capable of effective climate policies and are now often regarded as the liberal party to counter the far right AfD (11%, 11 seats), which didn’t manage to gain as much as was commonly projected, mostly due to the current scandal around former Austrian VP Heinz-Christian Strache [8].

All parties are now focusing on the upcoming elections in Brandenburg, Sachsen and Thüringen, which might bring heavier losses for SPD and CDU/CSU, but even higher results for AfD and the German Greens. After the European elections of 2019 Germany finds itself at a crossroads, as the country has to decide on the fate of the popular parties and whether they or the Greens can assume the dominant liberal voice on issues of climate change, immigration and the rise of the far-right.

[1] Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung. Interaktive Grafiken: Die Wahlbeteiligung bei Europawahlen. (Accessed 31.05.2019) https://www.bpb.de/dialog/europawahlblog-2014/185215/interaktive-grafiken-die-wahlbeteiligung-bei-europawahlen

[2] Der Bundeswahlleiter. Europawahl 2019. (accessed 31.05.2019) https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/europawahlen/2019/ergebnisse/bund-99.html

[3] Der Spiegel. Diese Lehren zieht die SPD aus ihrer Pleite. (accessed 31.05.2019) https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/spd-wahlanalyse-die-lehren-aus-der-pleite-a-1212310.html

[4] FAZ. Kevin Kühnert forder Kollektivierung von Großunternehmen. (accessed 31.05.2019) https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/arm-und-reich/kevin-kuehnert-fordert-kollektivierung-von-grossunternehmen-16166062.html

[5] Forschungsgruppe Wahlen. Wahlanalyse Europa 2019. (accessed 31.05.2019) https://www.forschungsgruppe.de/Aktuelles/Wahlanalyse_Europa/

[6]. FAZ. Kommt damit klar! (accessed 31.05.2019) https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/youtuber-rezo-sorgt-mit-anti-cdu-video-fuer-aufregung-16197065.html

[7] SZ. Wer hat in Deutschland wen gewählt? (accessed 31.05.2019) https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/europawahl-wahlanalyse-deutschland-1.4463723

[8] Der Spiegel. Nur der Osten leuchtet für die AfD. (accessed 31.05.2019)https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/afd-und-europawahl-warum-die-rechtspopulisten-nur-im-osten-punkten-konnten-a-1269392.html

Greece: Stavros Christos Papakyriazis

The Greek Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, aimed on a unification of the progressive powers in Greece, in order to outflank the center-right New Democracy. The latter managed to gain 8 seats in the EP, while SYRIZA only 6. The centre-left KINAL gained 2 seats, just like the far-left KEE. The two far-right parties managed to gain 3 seats in the EP.[7] Thus, the outcome of the EU elections managed to set a barrier for the Euroscepticism. Yet, it still remains to be seen if the dominant eurocratic powers in the EP will manage to address not only the populist crisis spreading across Europe, but also the question whether the severe repercussions of the upcoming Brexit for the EU are indeed inevitable. Regarding Greece, in particular, the outcome of the EU elections has highlighted the preference of the Greek majority towards the center-right party and also its frustration about the current leading party. This reality has set the basis for the upcoming national elections at the beginning of July in order to decide about the leading power in the Greek political scene.[8]

The fear of the populist rise within the European Union (EU), the subsequent increased euroscepticism and the unstable status of the EU due to the upcoming Brexit were some of the basic elements of the EU political scene prior to the occurrence of the EU elections in 26 May 2019. The centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and the centre-left European Socialists and Democrats (S&D) have been traditionally the two dominant political groups in the European Parliament (EP), providing “a pretty stable majority for the last couple decades”.[1] However, the latest rise of populism in the EU members has alarmed the Eurocrats regarding the challenge of maintaining the aforementioned status. A potential failure to secure enough seats so as to form together a majority in the EP would constitute the end of their ruling coalition. In practical terms, this could deprive the centralised groups from their power and transfer it to the Eurosceptics.[2]

Subsequently, we could observe a transition of powers from the EU institutions back to national capitals, since the Eurosceptics do not trust the vast amount of power entrusted in the EU.[3] Evidently, the preservation of rights so often has been the justification for taking them. Ultimately, the EPP managed to retain its position as the largest party in the EP with 213 seats, suffering a loss of 61 seats, while the S&D gained 191 seats.[4] The mainstream parties argued that the cause for the loss of many of their seats was the inefficient administration of the EU by the EPP during the crisis. Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU will be the largest group in the EPP. The S&D’s representation in Greece has dropped from eight to two seats, since it was surpassed by the far-left SYRIZA.[5] Now it remains to be seen whether the EPP nominee, Jean-Claude Juncker or the S&D candidate and President of the EP, Martin Schultz will gain the seat of the President of the European Commission.[6]

[1] Stephanie Burnett, The thing Eurocrats are most worried about with EU election results, euronews, (2019) Available at: https://www.euronews.com/2019/05/25/the-thing-eurocrats-are-most-worried-about-with-eu-election-results (Accessed at 29/5/2019).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Γιάννης Παλαιολόγος, Ελένη Βαρβιτσιώτη, Αριστοτελία Πελώνη, Ευρωεκλογές 2019, Καθημερινή, (2019) Available at: http://www.kathimerini.gr/playbook (Accessed at 31/5/2019).

[4] Dave Keating, The electoral fortunes of the EPP and the S&D, European voice, (2019) Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/the-political-parties-part-1/ (Accessed at 29/5/2019).Sites

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Γιάννης Παλαιολόγος, Ελένη Βαρβιτσιώτη, Αριστοτελία Πελώνη, Ευρωεκλογές 2019.

[8] In.gr, Νέος χάρτης στις εθνικές εκλογές: Κόμματα εξαφανίζονται, Βαρουφάκης, Βελόπουλος στο προσκήνιο, (2019) Available at: https://www.in.gr/2019/05/30/politics/neos-xartis-stis-ethnikes-ekloges-kommata-eksafanizontai-varoufakis-velopoulos-sto-proskinio/ (Accessed at 30/5/2019).

Hungary: Attila Nagy

In Hungary, the turnout was higher than ever before (2014-28,92%; 2019-43,36%) and the outcome just mildly altered the existing situation. They have in total 21 seats allocated on national bases in the European Parliament. The FIDESZ-KDNP conservative party won 13 seat which is 1 more than previously. The Democratic Coalition won 2 additional seats on the existing 2. The "Momentum" has two seats. The "Hungarian Socialist Party-Párbeszéd" lost one mandate, therefore, they will have only one seat remaining and the "Jobbik" also will have 1 representative compared to the previous 3. Despite their 51,14%, the FIDESZ-KDNP coalition has no clear place in the European Parliament after their (self)suspension from the European People's Party.

On the other hand, the opposition except for the "Jobbik" party expressed their wishes to join the liberal parties. Projecting these results on a National level, the FIDESZ-KDNP which already operates with a majority in the National Assembly would gain even more power. Orbán Viktor (Hungarian Prime Minister) called their victory "dignified" (MTV News 31.05. 2019). These results could be caused by their successful but rather aggressive campaign or by the fact that they won every previous election for the EP even when they didn't have the majority in the National Parliament. The accusation that FIDESZ-KDNP suppresses the opposition by controlling all the national media channels could be considered as influencing factor, but since there is no objectively approved evidence which would deny or confirm these actions it cannot be taken for certain.

Although the oppositions media presence is noticeably lower. FIDESZ-KDNP mainly wish to strength the anti-migration policies and Catholic values. They reflected on these goals in their campaigning with calling for a more nation-centric Europe, personally attacking left-wing politicians and spokespersons as well as liberal parties. They wish to continue the previously represented conservative position in the EP. Orban also pointed out that on this election more right-wing, conservative candidates been elected throughout the EU than before and this will help their cause in the EU. FIDESZ-KDNP already had the backing of the Visegrad Group (Slovakia, Czech Republic and Poland) on immigration policy and these results indicate that there will be additional supporters in the following period. Taking into consideration the overall results of the election, it probably will affect the selection of the President of the European Commission which could influence and guide the EU toward a more conservative position in the next five years.

Ireland: Alexander Fitzpatrick

The 2019 European Parliament Elections hold an important symbolism for the future of Europe and the direction that the EU will take. What is perhaps of equal, if not greater importance from the Irish perspective is how these elections highlight the Republic’s attitude towards the EU compared to the UK, and how the UK’s choice of MEPs reflects the attitudes towards Brexit which will directly impact the Republic via its border with Northern Ireland.

Looking to the ‘Green Wave’ that has crossed Europe, it appears that this trend is occurring in the Republic of Ireland. Ciarán Cuffe of the Green Party received the highest number of 1st preference votes for the Dublin Constituency. This trend that has crossed Europe is perhaps reflective of the growing importance of ‘climate change’ in political dialogue. Given the increased voter turnout across Europe, it may be assumed that the increased turnout could be a result of young voters rushing to the polls to voice their want for a more ‘green’ EU trajectory than has traditionally been the case.

It has been cited in several papers that the local or even European elections have been treated as a ‘protest vote’ against the Irish Government in Power. This was noted in the 2014 elections where Fianna Fail, the major party of the Irish coalition government during the onset of the recession, lost heavily as a result of the deep economic recession and IMF intervention. With this in mind, it is unusual that 4 of the 10 seats (at the time of writing, a re-count is ongoing in the Ireland South constituency with 3 seats yet to be filled as a result)* were won by Fine Gael, the government party. This is perhaps reflective of their strong stance on negotiating a good Brexit, absent of a hard border in Northern Ireland. It may also be noted that there is a lack of far-right or anti-EU party in Ireland that has had any success which differs greatly to our neighbours the UK or other major EU countries like France and Italy.

Regarding the impact that these EU elections will have on Ireland and the EU, I think it is clear that given the EPP and S&D have lost their majority in the EP that there is a major political shift taking place in the EU. I think the ‘Green Wave’ will have strong implications for future reforms of CAP. This may hold a strong impact on Ireland given that it is one of Europe’s largest beef and dairy producers. This political shift may also further encourage Ireland to meet its emissions targets.

*As of the editing of this article, Sinn Féin have withdrawn their recount request

Italy: Adrian Waters

The results in Italy were similar to the ones forecast by the opinion polls. [1] The right-wing League (formerly known as the Northern League) came first with 34.26% of the vote (equivalent to 29 seats in the European Parliament), followed by the centre-left Democratic Party with 22.74 % (19 seats), the catch-all populist Five Star Movement with 17.06% (14 seats), Forza Italia (Silvio Berlusconi’s centre-right party) with 8.78% (7 seats), Fratelli d’Italia (a minor right-wing group) with 6.44% (6 seats) and the SVP (South Tyrolean People’s Party) with 0.53 % (1 seat). Overall, the turnout was 54.50%, including the number of Italians who voted in the other 27 EU member states. [2]

Becoming the first party in Italy was the best electoral result in the League’s history. It drained votes from its coalition partner, the Five Star Movement, and the opposition with a hardline stance on immigration and effective social media tactics.[3] The League triumphed in the northern and central parts of the country [4] as well as in migrant ‘hotspots’ such a Lampedusa, the southernmost island where many migrants land [5]. New statistical analysis has shown that the party has gained votes from the young, women, ordinary workers and professionals and people living in poverty. [6] These factors prove that the League’s leader and Italy’s Interior Minister cum deputy premier, Matteo Salvini, has a popular foothold and that the country’s right-wing shift continues without many obstacles at the expense of the Five Star Movement whose results were worse than expected. Luigi Di Maio,the Movement’s leader and Italy’s labour minister cum deputy premier faced a vote of confidence by the party membership on its online platform because he was criticised for taking too much on his shoulders. Di Maio blamed the Movement’s poor performance on low turnout and a mudslinging campaign by the League.

In the end, he survived with the backing of 80 % of the rank-and-file who voted [7] What is clear to see though is that the Italian populist administration is shaken and some analysts are suggesting that there could be a snap parliamentary election soon, leading to a right-wing government. [8] However Salvini may be reluctant to leave the incumbent coalition since “he is ruling the political roost” and may not be able to push his own agenda if he aligned with seasoned politicians like Berlusconi. [9] Besides, it is too early to say for certain that a centre-right alliance could muster a parliamentary majority if there is another public ballot. [10] Nevertheless, both the League and the Five Star Movement are set to have disputes over several issues in the coming weeks as the former wants the latter to end its opposition to the construction of a high-speed rail line between Lyon (France) and Turin (northern Italy) and to a flat tax policy. [11]

As for the EU, the League is presently trying to forge a compact eurosceptic bloc in the European Parliament with other European right-wing populist parties such as France’s Rassemblement National and is close to striking a deal with the UK’s Brexit Party. [12] The gains made by eurosceptics have fostered a fragmented European Parliament, but there are profound differences within the radical right too. Salvini wants a quota system to redistribute asylum seekers across the EU, while others disagree [13], including the Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban whose top aide dismissed any chances of Fidesz (Orban’s party) working with a new far-right group. [14] Anyhow, with tensions rising between the European Commission and the Italian government over the latter’s budget plans [15], it is clear that it will not be business as usual in the EU institutions while the League and its allies try to get their own way at the expense of the other parties in the European Parliament.

[1] “Italy”, Politico, accessed 29th May 2019, https://www.politico.eu/2019-european-elections/italy/

[2] “Affluenza e Risultati”, Ministero dell’Interno, accessed 29th May 2019, https://elezioni.interno.gov.it/europee/scrutini/20190526/scrutiniEX

[3] AFP, “Far-right League victory in EU vote strains Italian government”, The Local Italy, accessed 29th May 2019, https://www.thelocal.it/20190527/far-right-league-victory-in-eu-vote-strains-italy-coalition

[4] The Local, “Italy's EU election results by region: Who won where?”, The Local Italy, accessed 30th May 2019, https://www.thelocal.it/20190527/italy-eu-election-results-by-region-who-won-where

[5] AFP, “Italy's migrant 'hot spots' vote for anti-immigration League”, The Local Italy, accessed 30th May 2019, https://www.thelocal.it/20190527/matteo-salvini-league-italy-eu-election-migrants-lampedusa-riace-ventimiglia

[6] Redazione ANSA, “Travaso di voti da M5s a Lega, ecco l'analisi del voto”, ANSA, accessed 30th May 2019, http://www.ansa.it/europee_2019/notizie/2019/05/27/travaso-di-voti-da-m5s-a-lega-ecco-lanalisi-del-voto_f01a3786-f3d9-4a06-9f48-a039cf0fe51e.html

[7] AFP, “Italy's Five Star Movement votes to keep Luigi Di Maio as leader”, The Local Italy, accessed 2nd June 2019, https://www.thelocal.it/20190531/italy-five-star-movement-votes-to-keep-luigi-di-maio-as-leader

[8] AFP, “Far-right League victory in EU vote strains Italian government”.

[9] AFP, “Will EU vote spell the end of Italy's populist rule?”, The Local Italy, accessed 30th May 2019, https://www.thelocal.it/20190526/will-eu-vote-spell-the-end-of-italys-populist-rule

[10] Giovanni Diamanti, “10 domande e risposte per capire davvero il voto del 26 maggio”, Linkiesta, accessed 30th May 2019, https://www.linkiesta.it/it/article/2019/05/28/elezioni-europee-chi-ha-vinto-chi-ha-perso/42313/

[11] AFP, “Italy's coalition government is one year old, but how much longer can it survive?”, The Local Italy, accessed 2nd June 2019, https://www.thelocal.it/20190531/italy-coalition-government-is-one-year-old-but-how-much-longer-can-it-survive

[12] Redazione ANSA, “Europee: sovranisti al lavoro per gruppo. Lega: 'Quasi chiuso con Farage' ”, ANSA, accessed 30th May 2019, https://www.ansa.it/europee_2019/notizie/2019/05/29/europee-sovranisti-al-lavoro-per-gruppo.-lega-quasi-chiuso-con-farage_f09562ce-8335-4eb7-9147-956c1ae59ddb.html

[13] Jon Henley, “A fractured European parliament may be just what the EU needs”, The Guardian, accessed 30th May 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/may/26/a-fractured-european-parliament-may-be-just-what-the-eu-needs?CMP=fb_gu&utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook#Echobox=1558909883

[14] Carmen Paun, “Hungary’s Fidesz dismisses cooperation with Salvini in the European Parliament”, Politico, accessed 30th May 2019, https://www.politico.eu/article/hungary-fidesz-dismisses-matteo-salvini-alliance-european-parliament/

[15] Silvia Sciorilli Borrelli, “EU steps up pressure on Italy to rein in public debt”, Politico, accessed 30th May, https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-steps-up-pressure-on-italy-to-rein-in-public-debt/

Latvia: Bella Bērziņa

Even though election results were close to what was expected based on the polls, they came out as a surprise and have already have led to some changes in local political scene. Last minute change happened when a liberal-conservative New Unity has gained 9% since late-April polls, which allowed it to get the biggest support of the voters among the other parties, even though they have lost 2 places in EP. Latvia holds 8 seats in European Parliament, and since the previous term, they were rebalanced between local parties. Turnout at the elections has increased from 30.12% in 2014 to 33.6% this year but still lagging behind 53.7% a decade ago.[1]

Overall, 4 MEPs will keep their positions and 4 will be newcomers representing centre-right wing parties. Among the re-elected candidates are Latvia’s former PM – Valdis Dombrovskis – of New Unity, who has served as a European Council Vice-President for Euro and Social dialogue, and another member of New Unity - Sandra Kalniete, who served as a Vice-Chair of the Group of the European People's Party in the European Parliament. Another 2 MEPs who will continue to serve in EP represent Latvian Russian Union and National Alliance (ECR and Greens).

Two parties that just recently successfully entered Latvian political scene – centre-right New Conservative Party and populist Who Owns the State? got below 5% and below 1%, respectively. While for populist party it was an expected loss, no one really expected New Conservative Party to be left with no places in EP, while this outcome was predictable based on the polls.

Results of elections have started to change a political scene in Latvia, since current Minister of Culture, who was elected for a second term in 2018, was elected to represent Latvia in EP, so she will leave her current position and a new minister will have to be assigned. Former Mayor of Riga – Nils Ušakovs and Vice-Mayor of Riga Andris Ameriks – both very controversial figures in Latvian politics, were elected to be MEPs from centre-left party “Harmony”, which mainly represents Russian-speaking population of Latvia. Former Mayor was suspended from his duties in April, 2019 by Minister of Environmental Protection and Regional Development due to possible violations of law while serving as a Mayor, however, did not resign until he was elected as MEP. Since he resigned, new Mayor of Riga was elected by Riga City Council. [2]

The new division based on political groups in EP: 2 ECR(-1), 2 EPP(-2), 2 S&D (+1), 1 Green and 1 New & Unaffiliated. [3]

[1] Central Election Commission of Latvia (2019) https://epv2019.cvk.lv/pub/velesanu-rezultati

[2] Ministrs atstādina Ušakovu no Rīgas mēra amata, LSM editorial staff ( 5 Apr 2019) https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/latvija/ministrs-atstadina-usakovu-no-rigas-mera-amata.a314895/

[3] Latvia https://www.politico.eu/2019-european-elections/latvia/

Lithuania: Gintvilė Bagdonavičiūtė

Lithuania finished the week of European election across the continent on the 26th of May holding election to the European Parliament. Even though Lithuania has only 11 seats in the Parliament, each seat is very significant to this very pro-European country.

Since 2004 the European Parliament elections in Lithuania take place together with the second round of presidential election, and this year was no different. The fact that the EP election coincided with the presidential election not only allows to save money on the organization of the voting day, but also makes Lithuanians one of the most active participants in the EU (apart from countries which have mandatory elections). However, having two very important elections comes with certain disadvantages. As all Lithuania becomes fairly focused on the new president, people often lack information and understanding of the importance of EP election. Nevertheless, Lithuanians are slowly getting more and more politically active (especially youth), there were a handful of debates on television, internet media and universities this year. But was that enough?

As mentioned, Lithuania has 11 seats in the parliament and this year 17 political parties, movements and committees were on the ballot. Starting from traditional ideological parties as conservative or social democratic parties, to populist one-issue parties, from pro-European committees to strictly Eurosceptical fired university professors. The results, however, were not surprising.

Most seats in the European Parliament were won by conservative party the Homeland Union (Tėvynės Sąjunga – Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai, TS-LKD), which got 3 seats and will join the European People's Party (EPP) in the EP. The most important support for the Homeland Union, according to many political experts, was that their presidential candidate former finance minister Ingrida Šimonytė was one of the competing candidates in the second round of the presidential election, attracting many supporters to the voting booths. Currently the majority party in the national parliament (Seimas), the Peasants and Greens Union (Valstiečių ir žaliųjų sąjunga, LVŽS) and traditional social democratic party (Lietuvos socialdemokratų partija, LSDP). The second person on LVŽS ballot was former basketball player and businessman Šarūnas Marčiulionis, who the next day after the election announced he will not take his seat in the EP. The next person on the list, scandalous economist Stasys Jakeliūnas will replace him and together with re-elected Bronis Ropė will join the Europeans Greens Party.

Despite having new faces among Lithuanian representatives in the EP – only 5 out of 11 MEPs were re-elected – Lithuanians have chosen many well-experienced politicians, including former prime minister, former ministers of defense, social security and current members of national parliament. Even though 11 Lithuanian MEPs will not play most significant role in the EP, we can be glad that pro-European parties will be supported by Lithuanian votes, balancing out increased number of Eurosceptic politicians from other EU member states

Luxembourg: Jorge Shaft

It was a shock that hasn’t been felt in the second smallest nation in the European Union, with the respected Luxembourger Wort newspaper describing the outcome as the ‘Blue Wonder’. For the first time in a long time, the centre-right Christian Social People’s (CSV) party of outgoing European Union Commissioner Jean-Claude Juncker has lost the popular vote to the politically liberal Democratic Party of the current prime minister Xavier Bettel.

The small country voted on 6 members of the European Parliament. Before the polls, 3 of these lawmakers were members of the CSV and thus sat in the EPP, the EU’s centre-right bloc.

However events of the past decade have not been kind to the party, culminating in ever more surprising electoral setbacks and defeat. In 2013, mired in the fallout of the Lux Leaks, a financial scandal that revealed significant tax evasion in the nation, the party found itself unable to form a coalition with any other grouping, despite being the single largest party, thus losing the prime ministership to the liberals for the first time since the 1970s.

The malaise has remained even as then prime minister Juncker pursued higher offices. In 2018 the nation once again re-elected Mr Bettel’s coalition, even as the CSV was once again the largest party, and on Sunday night the Luxembourg electorate punished it further, with the Grand Duchy’s first openly gay prime minister winning outright in the largest vote share- and thus a second coveted seat in the European parliament.

The new representatives will now consist of 2 EPP, 2 ADLE, 1 Green and 1 S&D party members.

No matter what the results would have been, a larger political change for the Grand Duchy loomed. For now the president of the European Commission will no longer be Luxembourg’s Juncker.

Malta: Simon

As one of the smaller nations in the EU, it may surprise many that Maltese politics is still a hotbed of action, and the EP elections were no different. The main upset came from the historic increase in support for the Labour party (S&D), winning well over 50% with one of the highest vote shares in Maltese history. This gave the incumbent government 4 of the 6 seats, whilst the opposition, the Nationalist Party (EPP) won the other 2 seats.

There were 8 other parties running, with some upsets in the Democratic Party (ALDE), the third party in parliament, where a campaigner Cami Appelgren won more votes than her own party leader. This dampened the already struggling party and proved that to PD voters liberal views were more enticing than the social conservative ideas the party was pushing for. Furthermore, whilst the far-right wave was touted in much of the EU, it failed to materialise in Malta, with Imperium Europa only receiving a little above 3% of the vote, with media sources claiming originally it could have secured double that.

This election already came fresh off the heels of the previous parliamentary election 2 years ago, giving Labour the highest vote share ever at the time. However, this election also showed that Labour had sticking power, with 16-18y olds also voting them in, being allowed to vote for the first time. This highlighted the implication that Malta is in for a long time with the Labour Party, even though Muscat has his eye on Brussels. With the Nationalist party still rife with internal struggles, it will take some differences for the opposition to surge back.

Netherlands: Sam Appels

The elections for the European Union had a surprising outcome in the Netherlands. One of the biggest losers from the previous national elections, the Labour Party (PvdA), became the biggest after the ballots were counted. Frans Timmermans, the Spitzenkandidaat who is running for president of the European Commission, was the face of the campaign of the PvdA. Timmermans argues in favour of reforms within the EU. Nevertheless, his voice is pro-EU. The EU- sceptical party the Party for the Freedom (PVV) from Geert Wilders lost their seats in the European Parliament; as did the Socialist Party (SP). After winning the elections for the Senate in the Netherlands, Thierry Baudet’s Forum for Democracy (FvD) did not manage to utilize its national victory within the European context. Although, the course of FvD in regard to a potential ‘Nexit’, is not always clear, it is fair enough to say that the party is sceptical towards the EU.

The party’s who are the most extreme in their attitude towards the EU lost relatively the most those European elections. The SP and PVV who are in favour of a Nexit and Democrats 66 (D’66) lost significantly. It seems that the Dutch voters feel more attracted to a nuanced sound about Europe – and the majority of the Dutch voters chose pro-EU. Although the Dutch liberal prime-minister Mark Rutte (VVD) and the Thierry Baudet tried to make it a two men show, the biggest winner of the elections was not one of them, but the Spitzenkandidaat from the Labour Party Frans Timmermans.

Despite the fact that Rutte and Baudet had a debate between them two on a prominent Dutch talk show the night before the elections, they did not take advantage of the time they got on national television. It was Frans Timmermans, the man with the most clear European narrative, who knew how to make the Dutch vote for him. By arguing in favour of working together on topics as climate change, social welfare and immigration, Timmermans distinguished himself from the other politicians with his clearly European narrative.

Poland: Jakub Stepaniuk

Sunday’s elections to the European Parliament served as the subsequent step of the electoral marathon between the last autumn local elections and the decisive voting to the Polish Parliament (Sejm and Senat), planned to be held in November this year. Unprecedented since 1989 extreme polarisation of the society between conservative-governmental and liberal-oppositionist camps igniting continuous disputes and consequent politicisation of the public life was genuinely translated into a sizeable turnout of over 45% (in comparison it was less than 25% in 2014 and 2009 EU elections).

Even though the three biggest committees which passed the required threshold of 5% proudly announced their huge victories, simultaneously, a slight sense of a disappointment was easily noticeable. Definitely, the least number of reasons to complain have the candidates of the Law and Justice Party (PiS) whose advantage over united opposition rose from 3% in first exit polls up to 7% in official results. The fact that over 90% of the electorate which voted for Andrzej Duda in 2015 decided to again elect PiS representatives clearly indicates a great success of Jarosław Kaczyński’s campaign and recent policies. The consequences of painful blows including paedophilia affair in churches or utter chaos in educational system eventually proved to be completely paltry for conservative electorate being successfully lured by another package of welfare benefits and national media propaganda. Low levels of volatility were also portrayed by social distribution of votes since the source of electoral harvest stemmed as usual from rural areas (almost 60%) and people with primary school education (70%). Traditionally polarised Poland was divided also by the geographical factor of an East-West split, portrayed by the following map:

EU elections served as well as a huge exam for the oppositionist campaign efforts. A relatively weak result of the united European Coalition (KE) including previously ruling Civic Platform, liberals, social democrats and agrarians will put into question a practical sense of the common participation in autumn elections. If the conclusions from mistakes committed during EU campaign are not be adequately analysed and instead of proposing an alternative programme the opposition will follow again the path of repeated governmental promises of economic benefits, current loss of seven percent to PiS might increase in autumn even more.

Yesterday’s results also proved the extent of a relentless electoral bipolarity present on the political scene since 2005. Liberal Spring (Wiosna) led by the charismatic leader Robert Biedroń who attempted to eventually break this tough muzzle despite expectations of a two-digit result afterwards hardly crossed the threshold whereas the activists of an exotic alliance of nationalists with anti-EU-abortions-vaccinations-LGBT-migration knights from Konfederacja found themselves half percent under the required level. United left submerged into even deeper malaise through getting one percent of the votes.

Portugal: Cláudia Silva

Portugal is one of the countries in which you can see that the EP election results are more about national politics than european issues. Even in the campaign trail, few were the deep discussions on Europe’s importance and future and engagement levels with voters were low. This, of course aligned with chronic good weather, gave the people excuses to not vote. The clear winner was the 68.4% abstention. Despite talks of nationalism across Europe, the country fought against that trend. The portuguese party system has been switched to the left since the 1974 Revolution ended Salazar’s far right dictatorship. The party furthest to the right with representation is CDS (part of the EPP group) that will hold 1 seat, which is considered a big defeat.

Also with 1 seat, Portugal secured one more position for the “Green wave”: PAN gained its first MEP. Regarding the far-left vote, the Left Bloc was the clear favourite. They elected two MEPs, double of the previous legislature. Behind came the Portuguese Communist Party, which now has one less seat than in 2014 (two in total). PSD, a centre right party (EPP group) has lost one seat which, then again, speaks more about the party’s national action (or, some might say, inability to create opposition to the governing Socialists). They secured 7 seats out of 21. The Socialists have gotten 1 more seat, totalling 9 and are the biggest portuguese delegation to the EP. This plays into the idea that the Government might be able to get a majority in the legislative elections next fall.

I’d highlight that 9 out of 21 MEPs are women, which provides further insight on the progressive nature of the Portuguese citizens. Of course, even if the results largely contribute to a pro-European EP, I’m convinced there is a substantial lack of information about the impacts of the Institutions and the importance of the European project

Romania: Daniel Petcu Mihnea

Romania’s European election results for this year dealt a major blow to the ruling Social Democratic Party (PSD), which came second with 23.39% of the vote in what was its weakest result in a decade. The entity comprising the main opposition, the National Liberal Party (PNL), who align themselves with the European People’s Party (EPP), earned 26.79% of the vote.

The voting day’s proceedings were defined by monumental frustration among thousands of Romanian expats who had been queueing up for hours on end at Romanian embassies and consulates across Europe in order to cast their votes, with many being unable to do so, and unfairly pinned the blame for such mishaps on the PSD-led Romanian government; such poor organisation was the result of a lack of coordination and poor communication between the various institutions which had opened their doors to voters. Furthermore, the day following the elections, supporters overwhelmingly rejoiced when Liviu Dragnea, former president of PSD, was sentenced to three-and-a-half-years’ worth of prison time for having arranged the payment of two party members employed in fake jobs.

Nevertheless, despite an opposition victory, it is very much unclear what their stance towards the European Union actually is, leaving the current relationship between Romania and Brussels uncertain. Quite worryingly, the majority of Rares Bogdan’s campaign involved the demonization of PSD and Dragnea especially as a Putin-like figure, with very violent verbal threats against the ruling party that would make one conjure up images of Nazi rallies. Equally, given the events that have unfolded in the aftermath of the election, namely and chiefly Dragnea’s arrest, it appears that this years European Parliament elections were used as an opportunity to smear political enemies and undermine PSD’s Eurosceptic and nationalist agenda. One of the biggest issues that I have with this frame of thought is that nationalism is nowadays equated to and conflated with right-wing extremism, even in its slight formulation, despite the fact that there is a significant body of research which highlights why this is problematic. Additionally, let us not forget President Klaus Iohannis’ (who used to be a member of PNL) blatant antisemitic disapproval of Prime Minister Viorica Dancila’s attempts to foster strong a strong relationship between Romania and Israel.

As a concluding remark, only time will tell whether PNL’s ‘triumph’ over ‘PSD-ist’ corruption will pay off vis-à-vis relations with the European Union, given the lack of exposition of a concrete plan of action and overabundant focus on PSD-ist corruption, when corruption is a phenomenon that is endemic to society and breeds mafia-like behaviour across the entire political spectrum (Russian oligarchism following the fall of Communism is a case in point).

Slovakia : Viera Zihlavnikova

The European elections in Slovakia continued to reflect deep divisions within the political spectrum both in the parliament and outside. Some parties want closer cooperation with the European Union while some were calling for closer relations with Russia and less rules from Brussels and possibly leaving the Union.

In comparison with the 2014 elections the voter turnout has slightly increased from approximately 13% to little over 20%, but still remains very low. Furthermore, the number of political parties which received sufficient number of votes decreased from 8 in 2014 to 6 in 2019.

Results were as following : PS+Spolu (20.1%) 4 seats, Smer (15.7%) 3 seats, LSNS (12.1%) 2 seats, KDH (9.7%) 2 seats, SAS (9.6 %) 2 seats, OLANO (5.3%) 1 seat.

The party with the highest percentage of votes, 20.1% and 4 seats in the European parliament, is a pro-European coalition of two different political movements “Progresivne Slovensko” (Progressive Slovakia) and “Spolu” (Together). They announced a joint candidacy at the beginning of 2019 and based their campaign on a clear message of being strongly pro-European and were openly critical of divisions created by the right-wing parties in Slovakia as well as in Europe and condemned politics of hatred.